A license to shoot an endangered black rhino. Concessions to club seal pups. Trophy elephants offered to hunters for $29,000.

These do not sound like activities in an ecofriendly tourist destination, yet all are sanctioned in a country whose conservation efforts are praised by the World Wildlife Fund and whose leadership was recently recognized as a "Gift to the Earth" by the World Wide Fund for Nature.

The country, Namibia, has drawn kudos and controversy with its pursuit of an independent approach to wildlife management that challenges both travelers and the industry to reassess what it means to be a responsible tourist.

Its policy of "sustainable utilization," rooted in Namibia's constitution, does not equate responsible wildlife stewardship with blanket protection of animals. In fact, the "utilization" aspect specifically embraces the monetization of wildlife by viewing, hunting and harvesting.

The policy has been credited with increases in wild animal populations that are the envy of much of the continent, and its success has changed the conversation to the point that, last year, Namibia played host to the annual summit of the Adventure Travel Trade Association (ATTA), a group fiercely committed to sustainability, and whose conference site is tantamount to an endorsement of the host destination's policies.

But even ATTA's reputation did not protect the organization from complex environmental politics. The conference hashtag was hijacked by local animal rights activists who tweeted dramatic photos of the seal harvest and messages calling for an international tourism boycott of the country.

But even ATTA's reputation did not protect the organization from complex environmental politics. The conference hashtag was hijacked by local animal rights activists who tweeted dramatic photos of the seal harvest and messages calling for an international tourism boycott of the country.

Namibia's environmental stewardship brings to the surface all the tensions that exist between the proponents of conservation and the desire for economic progress. The U.S. is currently the fastest-growing market for Namibia, including both eco-tourists and hunters. It's a constituency lured by different marketing messages, depending on whether they plan to shoot with a camera or rifle. (View a slideshow from Namibia here or by clicking on the images.)

The conservancies

Namibia's sustainable utilization program, which began in 1998, rests on a network of local conservancies in rural areas. Communities that enroll in the program are required to protect local animals within specific parameters, and in return, they can exploit local wildlife for the benefit of the community.

For example, a community could establish a game lodge, tours or other tourism-related concessions or, with the government's permission, issue a permit to shoot an elephant. Proceeds go to a community-related benefit such as a clinic, school or recreation center.

Government officials said that 46% of the country's land is now covered by conservancies. The economic benefits are only half of the program's design; it also recognizes and tries to resolve conflicts that often arise between communities and forms of wildlife viewed as a threat to livestock.

Or tempting targets to poach.

Metumbo Nandi Ndaitwah, Namibia's minister of foreign affairs, addressed ATTA and bluntly stated, "If there is no trophy hunting, there is no conservation. We will not shy away from it."

Metumbo Nandi Ndaitwah, Namibia's minister of foreign affairs, addressed ATTA and bluntly stated, "If there is no trophy hunting, there is no conservation. We will not shy away from it."

The elephant population in Namibia rose from 7,500 in 1995 to 16,000 today, she said, and only 90 are used each year for "trading purposes."

The country is particularly proud that it has converted self-confessed rhino poachers into rhino protectors, but considerable controversy erupted last year when a permit to hunt an endangered black rhino was granted to a Texas hunting club. The permit was to be auctioned off to a club member, with the expected proceeds of between $250,000 and $1 million to go specifically for rhino conservation in Namibia.

The president of the Humane Society in the U.S. was quoted as responding, "If these are multimillionaires [who] want to help rhinos, they can give their money to help rhinos. They don't need to accompany their cash transfer with a high-caliber bullet."

All black rhinos belong to the state, Ndaitwah said, and they have seen a "tremendous rebound. When rhinos get old, they can go to a trophy hunt." The country issues up to five rhino permits per year.

Sealing and ATTA

Shortly after announcing the ATTA summit in Namibia, the organization's president, Shannon Stowell, was contacted via email by two local anti-sealing groups, alerting him to the clubbing.

"I replied that it sounded like an issue, that it was troubling, and let's have a conversation," he said. "One said they respectfully disagreed with our decision [to hold the summit in Namibia]. The other started a Change.org boycott of Namibia."

"I replied that it sounded like an issue, that it was troubling, and let's have a conversation," he said. "One said they respectfully disagreed with our decision [to hold the summit in Namibia]. The other started a Change.org boycott of Namibia."

Stowell sees the issue as complex. "It's a tough story and does deserve a discussion," he said. "But the extreme of a boycott and cutting off a complex system at the knees endangers all of Namibia's gains. It seems shortsighted."

The government declined to discuss the seal harvest on the record, a decision Stowell said he understood better after the anti-sealing group hijacked the conference hashtag.

"The government is now in a completely defensive position," he said. "There's no room for dialogue."

Backsliding up Big Daddy

Paradoxically, the country's unique and strongest assets are not necessarily related to wildlife. Namibia's Etosha National Park contains "the big five" -- elephants, rhinos, buffaloes, lions and leopards -- and other areas offer enough game, from meerkats to Hartmann's zebras, to keep game-seeking visitors engaged.

But neighboring Botswana's parks provide much greater variety in scenery and species, higher animal density and a range of lodging and accommodations that will please the fussiest visitor.

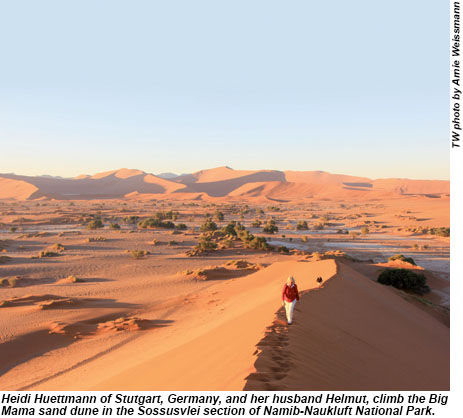

Namibia, however, offers sand -- sand like no other nation on Earth. Shifting dunes, petrified dunes, coastal dunes and climbing dunes with names both clinical (Dune 45) and challenging (Big Daddy).

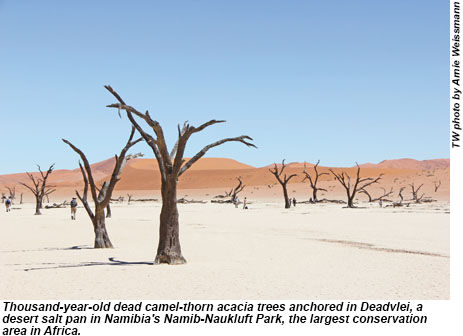

Sand alone would make the country worth the considerable investment in time that it takes Americans to travel there. The adjacency of 1,250-foot Big Daddy to Deadvlei, a salt pan pierced with 1,000-year-old dead camel-thorn acacia trees, provides a soft adventure thrill in one of the most surreal landscapes on Earth.

Climbing the dune requires a bit of effort -- for every step up the spine of the dune, one backslides half the gain in loose sand -- and most visitors are satisfied to climb only partway.

Climbing the dune requires a bit of effort -- for every step up the spine of the dune, one backslides half the gain in loose sand -- and most visitors are satisfied to climb only partway.

But making it to the top offers ample rewards: One imagines that 360-degree views on Mars are not much different, while the white-crusted salt pan below looks like nothing so much as an ice rink, and the tourists on it like skaters.

The walk or run down the face of Big Daddy toward Deadvlei below is one of the more enjoyable things a human being can do, and more than enough compensation for the climb. Once at the bottom of the dune, the approach to the dead trees poking out of bright, white earth at the far end of the pan inspires a happy cognitive dissonance, a Siberian winterscape under a desert sun with a backdrop of multihued dunes.

All or nothing

Tours of the host country are an important part of ATTA summits, and in most post-tour conversations, delegates focused on visits to the dunes, conservation areas or parks. The hunting controversies seldom arose. Nonetheless, whenever a government representative was on stage, the talking points focused on sustainable utilization.

The speakers might have felt a bit more defensive than was warranted in front of that audience, but they were clearly aware they have critics who have taken an uncompromising stance, particularly when it comes to seals and rhinos.

Two years ago, in a nod to such critics, the government enlisted an ombudsman to look into the sustainability of its sealing practices. The ombudsman blessed the seal harvest but recommended various changes in technique and oversight to make it more humane.

Having gained no relief from its critics after the report was issued, the government appears so alienated by the anti-sealing forces that it is loath to give them even the smallest victory. The government believes the correctness of its position is borne out in healthy animal populations, regardless of the treatment of some individual animals. Likewise, it sees no sense in giving up the money that seal and rhino hunts bring in.

The argument a government official gave me for its uncompromising positions -- "For the other side, it is emotional" -- may be true, but that perhaps adds to the potency of the opposition rather than detracts from it. There is no cuter animal than a baby fur seal. And if there is one endangered animal whose story is widely known, it is the rhino and its misfortune to have a desired horn.

To outsiders, it may be confusing that Namibia has chosen these particular battles to fight. Does it want to ultimately be characterized as killers of baby seals and rhinos?

At this point, for both sides, the battle is all or nothing, and as long as it is, Namibia's tourism efforts could prove to be a bit like climbing Big Daddy, backsliding halfway for every step up and forward.

Email Arnie Weissmann at aweissmann@travelweekly.com and follow him on Twitter.

View a video from atop Big Daddy here or below.